In the fifty years of stewardship, resonance, and interpretation of change, geologic forms, and animal life, Joy Fox has become indigenous to Rancho Linda Vista: her home, studio, and community of the arts in Oracle, Arizona. Since 1968 the ranch has served as a sacred origin for her sculptures and her story, and continues to offer creative shelter to the many artists who live and work there. Fox’s hands have pulled the clay from the desert washes, her feet know the trails by heart and still take her to those small nemetons where her beloveds listened and painted.

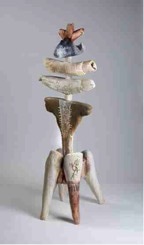

Walking among the sculptures of Joy Fox one can almost hear the hum of ancestral voices. These works, more than mere sculptures, are beings, watchers, and witnesses of time and transformation. According to Tibetan mythology, magically conceived images and creations can become corporeal beings (tulpas) capable of straddling both the physical and spiritual world.

“Once the tulpa is endowed with enough vitality to be capable of playing the part of a real being, it tends to free itself from its maker’s control. This, say Tibetan occultists, happens nearly mechanically, just as the child, when his body is completed and able to live apart, leaves its mother’s womb.” (1929) Buddhist Alexandra David-Néel

[The pieces] end up having a conversation amongst themselves [and] take on a life of their own. I don’t know which one I’ll use until after they’re fired because once it's fired, it takes on another life that is very different. It comes alive. (Joy Fox, personal conversation, 2013)

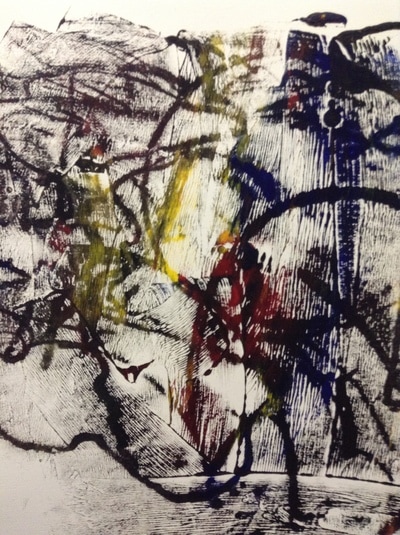

Each finished sculpture holds the presence of a uniquely conjured thought form, a “shamanic tulpa”, revealing external markings and scripted incantations scratched onto the surfaces and into the folds; sometimes understandable and poetic, sometimes indecipherable as a lost language suggesting conveyance from an ancient internal world.

Joy Fox’s studio is luminous and airy, offering loose but protective shelter while Possibility and Providence assist her open and accepting nature in the kneading and folding of the clay. Filled with her large and small figures, every piece that surrounds her seems in the lineage of the earliest creators, each joining the continuum of her lifelong conversation with primordial elements and the Ancients. The stray parts of unconstructed totems that fill the crates and corners of the studio, though in a state of dismemberment, are complete works themselves and more like artifacts that were once part of a former, larger body. They now wait to coalesce into another in a new cycle of life and seem to want to have their say in how they are re-membered within the work.

There are times if I'm working a piece . . .and it's just not making any sense . . . I’ll start on something else, then look over at it and it will tell me what it needs. (Joy Fox, personal conversation, 2013)

Historically, clay has been used by many cultures as a connective medium to the spirit world. It is believed that many of the oldest clay figures were used in magical and ritual ceremony as symbols of goddess or god and symbols of power over the natural world. Fox’s sculptures are recognizably (to those who are attuned) totems of power. Muse, gods, and goddesses frequently appear as images inscribed on the surfaces, or even personified in the constructed being, but Orpheus (sometimes referred to as the “patron saint” of poets, artists, musicians, and philosophers) shows up throughout her process as well to blandish all aspects of transformation and transmutation, while the clay becomes art.

With clay gathered from varied locations, salvaged metal once serving machine is now summoned by Fox to contribute other movements, gestures, and catalysis through her divine artistic language. Combining the clay crystals of life with a substance that first showed itself to humankind by falling from the heavens on fire, charged with magical and divine power, and later known as the blood of the earth—iron, the work acquires a harmonic voice in her alchemical invocation.

The invitation of the clay, as it is pliable and willing, is a call for Fox to re-remember in the most primal way; even now in late career, she is captured by the muse and cannot deny the invitation. Compelled to speak through clay as her native language, her process of handling, manipulating and sculpting clay, taps into primary modes of expression that may have evolved before verbal language. These modes of expression are linked to actual feeling and memories that were encoded through touch and movement. Her anomalous forms resonate to the creatures and elements of nature, gods, and time. Fox converses with the ancestors as she works the clay of life, her genetic material and that of the Ancients in crucible and by fire. Fire then assists in releasing, releasing Fox to the very same time and space of the first potters and all others in between.

Orphism teaches that human souls are divine and eternal and yet fated to repeated cycles of grieving in order to evolve and advance. With each stage of development, there is a looking back at the unsaid, undone, or unresolved; a letting go and then a move forward. When art becomes a path of discovery, self-awakening, and spiritualization it moves within these transformative cycles. Jungian scholar Robert Romanyshyn characterized six Orphic Moments in transformative work and of these six the last two include Dismemberment and Individuation. These two Orphic stages aptly sum the character and creative space of Joy Fox’s call to transformation as a deep attentiveness to the life stirring within the inanimate. She sits in readiness for her own intimate conversation with the ancestral voice of clay, and the soul-full influence of fire to be present in “spiritualizing” the piece. For this to happen Fox must face dismemberment and follow the soul of the work. Reconstructing the bones that have returned from the dust of the earth, returned from the fire of the universe now require something of Joy Fox in order to be spiritualized, the moment of confronting dismemberment after the fire, after the bones have been conjured requires that Fox let go of the work and imagine it in a different way.

The clay has now been worked, formed, carved, and fired into the heads, arms and trunks of the sculptures. Up until now the ancestors have held a subtle sway, up until now she has been “with child” and pregnant with a “being” she can’t see or know. Fox sets the fired pieces out and waits, letting go of her own involvement in the individual forms and surfaces knowing that they will now take on a different reality, the work like the tulpa will come into its own. There is a very subtle process of “re-contextualizing” and detaching, a moment of grief even, and then movement to the stage of individuation when the pieces become an individual. It would follow that once that happens, as Fox has indicated, she is completely done with the piece and wants it to leave the studio either to be shown or live elsewhere.

From this perspective, one can understand Fox’s entire process as a reversal of the process of death and a movement toward rebirth, with true sacrifice existing as it did for Orpheus, in mourning and grief. Dust, earth, and clay as the “forgotten” nourished by water submit to the energy of creator and voices of the continuum to form and resurrect the bones. When fire releases back from the world of the dead and the past, grief must be revisited and re-membered. Transformation and spiritualization comes from the process of remembering, and then moves to individuation bringing the work into being.

The earth and the iron of the clay have become absorbed into the skin of Fox’s hands and arms as she gathered the dust from the scatters of time to stand and witness again as sculptured sages. Their stories now can be known from their one or many faces, their scarred surfaces of mapped journey, and the animal parts that assist them. Broken pieces among the flowers and stones outside the studio remind us that the clay will return to earth eventually, back to source, as will we.

At the highest ground near Rancho Linda Vista a new grouping of Fox’s giant talismans have been placed; tiny lights illuminate the insides of these beings. They would light the hilltop in the lonely darkness of the desert. Are they now able to light back to the stars and the continuum? Fox’s wizardry, her masterful alchemy, and intuitive ability to converse with primordial elements in order to bring forth these mythic and magical metaphorms, create a living presence that is arresting and hallowing. In witnessing her magnificent artistry, we are simultaneously bowing to Mystery Herself.

Diane Lucille Meyer, PhD, Artist, Artist Researcher, Transpersonal Psychologist

RSS Feed

RSS Feed