On December 9, 1999, I left my life of 23 years and moved to a very small inexpensive apartment in downtown Tucson. When I arrived at my new place, a yellow duplex with green trim, I spent the next 4 days in complete despair. As I unpacked what little I had, I decided to arrange my rock collection on the waist-high pony wall outside between my apartment and the neighbor’s.

I placed the stones in a circle as a way of asking spirit to come in and help me. Then I left the circle alone and continued to find my way in my new life. A few days later, I noticed my stone circle, and someone (I later learned the person living next door) had taken a sunflower and laid petals between all the stones with the center of the flower in the center of the circle. This brought me to tears. I was overwhelmed with a feeling of love and comfort. At that, I decided to add a piece of blue yarn I had just untied from a bundle of papers and I wove it meandering in and out of the petals and stones in a way that felt like I was communicating our connectedness. The next day the woman next door had added some small sprigs of rosemary to the sequence.

This went on for several days. Sometimes the wind or a cat disrupted it, but we continued. There would be times when we would not contribute much and then times when this conversation was very active. Ultimately it had a profound effect on my sense of not being alone and faith that my prayers have been heard. I never took photos of our conversations, but to this day I will reenact this exchange as a means of self-soothing, quieting my verbal thoughts, or simple prayer.

The woman who lived next door was named Siu and she sensed my sadness through the walls that separated us. I only knew her first name and I have no idea what became of her. She was a true gift from Providence. She reached out without a verbal language to tell me she hears and that I still existed.

In my dissertation research collection of nonverbal data held my original objective of evoking creativity and a sense of “other” as my participant in order to engage in a creative conversation that was random and intuitive. Deciding how exactly to achieve this was the challenge. My personal experience within my own work, as well as the experience I had with my neighbor Siu utilizing found objects gave me information about what the exercise should contain, as well as what the exercise should not.

It seemed essential that both my participant and I use a common language, if I used watercolor and she clay it could not work because clearly everything that involved her medium would feel like other to me and I would not be able to discern the third participant. Then, if we both used watercolor, there was no way to clearly assess that my participant has the same fluency that I do with the medium. Using found objects soon revealed that they still carried their basic context to the conversation; feather was feather and not a stroke of umber or a response of texture. There was also difficulty describing the task and the idea of responding to the evolving environment as objects were placed. I had planned to photograph the images to capture the engagement of both of us with other or what we agreed was creativity but without the participant’s understanding deep engagement (not just randomly placing objects) I was at a loss.

Instead, I decided to work with my participants with no objects, no tools, devices, or implements. I decided we would merely use both our hands in intuitive movements and gestures over the paper, beginning and stopping when the moment felt right. We would ask Creativity to flow through us and guide our movements as its own brush strokes.

The process I used was adapted from Deborah Koff-Chapin’s Touch Drawing therapeutic technique that evolved along the same exploratory path that I originally wanted to follow with this inquiry. She describes how the process came to her:

The idea that neither my participant nor I could see what we were creating was intriguing. We could not base a movement on anything aesthetic in the work, we moved without judgment or a sense of what our finished work would look like. I did not set a rule to start and stop within any amount of time, we worked fairly quickly, and we could work solo or together simultaneously as we wished. This was a process as free from rules of art, free as I could arrange. I explained to my participant that the finished product would contain what I might call our creative DNA in that it was something from our artistic instinct and of us, but outside of our evolved system of responding in images.

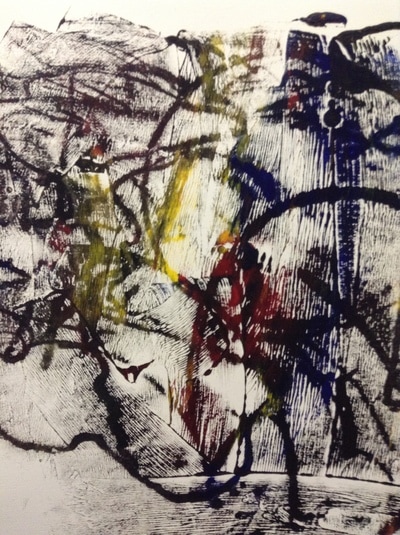

Water-soluble oil paint was rolled out on to a piece of Plexiglas and I chose to use 140 lb. watercolor paper as the barrier between the image and us. The paper was laid over the paint and we moved with our hands, arms, elbows, rhythmically over the paper.

My questions for this exercise were, as we see the marks and movements of both of us, did we feel a sense or a presence of other in this co-creation? If so, where or how? And, what thoughts or images came to mind while we engaged in this event? These are the images that evolved from our engagements (see below).

It is important to note that even though the participants and I were amused by the images we could pull out of these works (such as a dancing woman or a bird) we refrained from labeling them so as not to ultimately limit their gifts.

While this process of presentation unfolded, I was haunted by a dreamlike image that would recur as a cage containing a yellow finch. At times, the image was in full focus and other times hazy and vague but this cage represented my method and though horrified by the thought of method being so restrictive, I pressed further to try and understand what the image was trying to tell me.

Cages are meant to trap or contain, but they also are meant to keep tender fragile beings safe, they can provide safety to the outsiders as well. As this cage and bird became a stronger metaphor for my research I asked, “What is it I am attempting to capture? What am I protecting within this research? What am I avoiding or considering as dangerous?” and “Is this cage even necessary?” Meditating on the cage, I made sure the cage door always remained open. Sometimes the finch would be inside singing, and sometimes he would not be in sight but I could still hear his song in the distance.

The journal entries, reflective and embodied writing, and poetry expose moments of clarity, crisis, growth, and transformation that give voice to the work that assists me even now. Yet presenting the data as an intuitive researcher, I found the beats of the presentation very closely related to my dance as a painter. I begin with the most familiar and meander outward to the more abstract and intangible. This intuitively leaves open avenues for finding meanings and connections, where that finch is free to do as he/she pleases.

Koff-Chapin, D. (n.d.). Discovery of touch drawing. Retrieved from http://www.touchdrawing.com/touchdrawing/discovery

I placed the stones in a circle as a way of asking spirit to come in and help me. Then I left the circle alone and continued to find my way in my new life. A few days later, I noticed my stone circle, and someone (I later learned the person living next door) had taken a sunflower and laid petals between all the stones with the center of the flower in the center of the circle. This brought me to tears. I was overwhelmed with a feeling of love and comfort. At that, I decided to add a piece of blue yarn I had just untied from a bundle of papers and I wove it meandering in and out of the petals and stones in a way that felt like I was communicating our connectedness. The next day the woman next door had added some small sprigs of rosemary to the sequence.

This went on for several days. Sometimes the wind or a cat disrupted it, but we continued. There would be times when we would not contribute much and then times when this conversation was very active. Ultimately it had a profound effect on my sense of not being alone and faith that my prayers have been heard. I never took photos of our conversations, but to this day I will reenact this exchange as a means of self-soothing, quieting my verbal thoughts, or simple prayer.

The woman who lived next door was named Siu and she sensed my sadness through the walls that separated us. I only knew her first name and I have no idea what became of her. She was a true gift from Providence. She reached out without a verbal language to tell me she hears and that I still existed.

In my dissertation research collection of nonverbal data held my original objective of evoking creativity and a sense of “other” as my participant in order to engage in a creative conversation that was random and intuitive. Deciding how exactly to achieve this was the challenge. My personal experience within my own work, as well as the experience I had with my neighbor Siu utilizing found objects gave me information about what the exercise should contain, as well as what the exercise should not.

It seemed essential that both my participant and I use a common language, if I used watercolor and she clay it could not work because clearly everything that involved her medium would feel like other to me and I would not be able to discern the third participant. Then, if we both used watercolor, there was no way to clearly assess that my participant has the same fluency that I do with the medium. Using found objects soon revealed that they still carried their basic context to the conversation; feather was feather and not a stroke of umber or a response of texture. There was also difficulty describing the task and the idea of responding to the evolving environment as objects were placed. I had planned to photograph the images to capture the engagement of both of us with other or what we agreed was creativity but without the participant’s understanding deep engagement (not just randomly placing objects) I was at a loss.

Instead, I decided to work with my participants with no objects, no tools, devices, or implements. I decided we would merely use both our hands in intuitive movements and gestures over the paper, beginning and stopping when the moment felt right. We would ask Creativity to flow through us and guide our movements as its own brush strokes.

The process I used was adapted from Deborah Koff-Chapin’s Touch Drawing therapeutic technique that evolved along the same exploratory path that I originally wanted to follow with this inquiry. She describes how the process came to her:

- Within several weeks the seed that had been germinating in my being burst forth in the form of Touch Drawing. On the last day of my last year in school, I was helping a friend clean an inked glass plate in the print shop. Before wiping the ink off the plate with a paper towel, I playfully moved my hands over the towel, and lifting it, saw lines which had been transferred to the underside of the towel by my touch. Lines coming directly from my fingertips! I laughed hysterically with this discovery and crawled around on the floor, gathering up more discarded paper towels. In a state of ecstatic revelation, flowing lines poured from my hands. Like the willow in the sand, they were a natural extension of my being onto the page, a record of each moment as it passed. Within minutes, I was drawing faces with both hands. My ever-changing soul was being reflected before me, childlike and primitive, honest and direct.

- Although this experience had the appearance of simply being play, under the surface was something profound and powerful. It was as if I was receiving a gift from outside of time, from an invisible knowing presence. (Koff-Chapin, n.d., para. 9)

The idea that neither my participant nor I could see what we were creating was intriguing. We could not base a movement on anything aesthetic in the work, we moved without judgment or a sense of what our finished work would look like. I did not set a rule to start and stop within any amount of time, we worked fairly quickly, and we could work solo or together simultaneously as we wished. This was a process as free from rules of art, free as I could arrange. I explained to my participant that the finished product would contain what I might call our creative DNA in that it was something from our artistic instinct and of us, but outside of our evolved system of responding in images.

Water-soluble oil paint was rolled out on to a piece of Plexiglas and I chose to use 140 lb. watercolor paper as the barrier between the image and us. The paper was laid over the paint and we moved with our hands, arms, elbows, rhythmically over the paper.

My questions for this exercise were, as we see the marks and movements of both of us, did we feel a sense or a presence of other in this co-creation? If so, where or how? And, what thoughts or images came to mind while we engaged in this event? These are the images that evolved from our engagements (see below).

It is important to note that even though the participants and I were amused by the images we could pull out of these works (such as a dancing woman or a bird) we refrained from labeling them so as not to ultimately limit their gifts.

While this process of presentation unfolded, I was haunted by a dreamlike image that would recur as a cage containing a yellow finch. At times, the image was in full focus and other times hazy and vague but this cage represented my method and though horrified by the thought of method being so restrictive, I pressed further to try and understand what the image was trying to tell me.

Cages are meant to trap or contain, but they also are meant to keep tender fragile beings safe, they can provide safety to the outsiders as well. As this cage and bird became a stronger metaphor for my research I asked, “What is it I am attempting to capture? What am I protecting within this research? What am I avoiding or considering as dangerous?” and “Is this cage even necessary?” Meditating on the cage, I made sure the cage door always remained open. Sometimes the finch would be inside singing, and sometimes he would not be in sight but I could still hear his song in the distance.

The journal entries, reflective and embodied writing, and poetry expose moments of clarity, crisis, growth, and transformation that give voice to the work that assists me even now. Yet presenting the data as an intuitive researcher, I found the beats of the presentation very closely related to my dance as a painter. I begin with the most familiar and meander outward to the more abstract and intangible. This intuitively leaves open avenues for finding meanings and connections, where that finch is free to do as he/she pleases.

Koff-Chapin, D. (n.d.). Discovery of touch drawing. Retrieved from http://www.touchdrawing.com/touchdrawing/discovery

RSS Feed

RSS Feed